- Home

- William Haggard

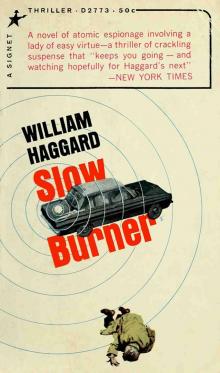

Slow Burner Page 7

Slow Burner Read online

Page 7

No, he decided, nothing could come of that.

Chapter 4

For Sir Jeremy Bates the meeting of the Commission had not gone too well. He had arrived a little early and had had time for a word with the Secretary. He learnt that besides the Minister, besides himself and the scientists, Elton would be attending and Professor Wasserman. There would be several others including Holsteiner, but the Secretary and Sir Jeremy had exchanged a glance about the others. They were evidently satisfied that the effective strength of the Commission would be present.

Sir Jeremy sat down, but his contentment was short lived. The Commission’s Secretary slid up to him again. ‘The Minister has just telephoned,’ he explained. ‘He asked me to tell you personally that he will not be able to come after all.’

‘Thank you,’ Sir Jeremy said. He concealed his disappointment, for this was disappointing news. It was a bad beginning. It was true that Gabriel Palliser took his seat as the Commission’s chairman only exceptionally, but Sir Jeremy considered that today was a clear exception. He felt himself entitled to support. Moreover in the Minister’s absence he was Deputy Chairman, and his experience was that the chair was a poor position from which to conduct a defence.

The thought surprised him, for he hadn’t before admitted to himself that he might be put upon the defensive. He shrugged a little irritably. It was his own paper which was before the meeting: that would be an excuse for declining to preside. Holsteiner would do it, of course, and gladly; Holsteiner owned something more than a taste for the appearance of authority.

Sir Jeremy began to think about his paper as the room filled. He knew that it had been circulated, by special messenger, late on Saturday, and some of the Commission would have read it on Sunday—all would have read it, he considered, whose opinion mattered. It was a creditable paper, dispassionate and factual. But not, Sir Jeremy reflected now, as factual as it might have been. The trouble was going to be that there simply weren’t enough facts.

He quietly made his arrangements with Holsteiner, and the new chairman tapped upon the table. At once and without fuss there was attention. The Nuclear Development Commission was in session.

Holsteiner turned first to William Nichol. ‘I think we must eliminate theft,’ he said.

Sir Jeremy was conscious of a moment’s irritation. His paper had been a most careful paper; it had pointed out that theft of Slow Burner was an hypothesis which did not cover all the facts; but it had not said tout court that theft was impossible. Sir Jeremy was a little piqued.

‘I think so,’ Nichol agreed. ‘We are humanly certain that no Slow Burner has been stolen—certain enough, I should say, to put the onus of showing that it has upon anybody who wishes to take that line. Though as you know to do so would hardly help. For though theft might explain the Dipley epsilon rays until about noon on Friday and a second and even more hypothetical theft the rays which are being recorded at the moment, no theft explains the period during which there wasn’t a gramme of active Slow Burner in the country. And during that period we were still receiving recordings. From Dipley, and from Dipley alone. And intermittently—that is another difficulty.’

‘Intermittently?’ Sir Jeremy asked sharply. ‘I did not know that.’

Holsteiner did not seem to be greatly impressed. If such a thing had been conceivable you would have said that he was waving Sir Jeremy’s interruption aside. ‘It is a detail,’ he said, ‘puzzling but not essential to the immediate point. Which is that theft must be excluded.’

There was a murmur from the scientists. It was polite and unemphatic, but it was evident that they didn’t consider that theft could be any sort of explanation.

Nor, it became clear, did the rest of the Commission. Finally Holsteiner put it from the chair with his usual deliberation. ‘Then we must assume that somebody is either making Slow Burner at Dipley or is simulating it.’ He smiled a little sourly. ‘The former I propose with your permission to discount. We have all of us seen a Nuclear Energy Centre and many of us know something of what is involved in manufacturing Slow Burner. We are not going to believe that it can be made in some amateur’s laboratory. That would be magical, and magic, I suggest, is a little outside our competence.’ There was another murmur of assent. ‘In which case,’ Holsteiner went on, ‘somebody is simulating it. How, we do not know, nor why. Those will be matters of fact.’ He turned towards Charles Russell. Colonel Russell was attending the Commission by invitation. ‘Can you help us a little further?’ he asked.

‘Not very much, I’m afraid. Certain steps are being taken which you will not wish to be wearied with. But by this evening we should know.’

‘But how much shall we know?’ It was Elton who spoke, Elton of Conventional Fuels. Sir Jeremy watched him closely. Elton, he knew, was brilliant, barely forty—very young to be a Permanent Secretary. And Conventional Fuels wasn’t, nowadays, a great Department; it was slipping a little, but slipping increasingly. Whereas the Ministry of Development would be a tremendous plum if he, Sir Jeremy . . .

Sir Jeremy continued to watch Sir Harold Elton very carefully.

Charles Russell was answering the question. ‘Perhaps I shouldn’t have said “know”,’ he was saying. ‘Perhaps I should have said “confirm”. For I am hopeful that by this evening we shall have confirmed that somebody is simulating Slow Burner from Dipley. I too would suggest that as a working hypothesis.’

Holsteiner nodded. ‘We have accepted it,’ he said briefly. He looked about the table. ‘And we must assume for this morning that it has been established.’ A dozen heads nodded. ‘Which brings us,’ Holsteiner went on, ‘to matters of speculation—how, who and why? How is something about which Russell may be able to tell us a little more shortly. But who and why . . .?’ Holsteiner glanced again around the table. ‘Would anybody care to guess?’ he inquired.

There was a notable silence, and Holsteiner looked again at William Nichol. ‘Nichol?’ he suggested. ‘You wouldn’t care to speculate?’

‘I would not.’

‘And nor would I. But we must put it on record, I suppose, that there can’t be more than a dozen men in the country capable of such a thing.’

‘Of whom I am one,’ Nichol said. His voice was formal, and the Commission accepted the statement formally. ‘Quite,’ Holsteiner said dryly. ‘We note the possibility without comment. No comment is necessary.’

There was another and considerable silence which Elton finally broke. ‘And when Russell has discovered this whatever it is, what then? What are the possibilities of action?’ He was looking directly at Sir Jeremy as he spoke. His manner was short of open hostility, but it was the manner of a man aware this question was an awkward one. Sir Jeremy reflected that Elton wasn’t usually a man to force an issue. He obliged himself to return his inspection. Elton’s face was impassive, but Sir Jeremy decided that he had declared himself. Here then was an enemy. Sir Jeremy rallied his senses. His brain was clear enough, but he knew that he needed more than his brains. He must be sensitive, aware . . .

‘Possibilities of action?’ he repeated carefully. He knew perfectly well what Elton was leading to.

‘Precisely. We are assuming that Russell will shortly be able to tell us what, and conceivably how. But we are by no means entitled to assume that the answers to those questions will also tell us who or why. And evidently those are the real problems. We haven’t, as I understand it, a great deal of time—almost certainly not time for the ordinary procedures.’

‘And you would suggest?’ Sir Jeremy asked. He knew what was coming, but he had decided that it would be impossible to duck.

‘I suggest that it would be well to consider the special powers; to consider the Nuclear Security Order.’

This was what Sir Jeremy had feared, and indeed it was a very awkward matter. The special powers were something which Parliament hadn’t liked at all. Every lawyer, Left or Right, had rumbled uneasily, and certainly it was without precedent to invest a Minister, in peace, with powers to

set aside the ordinary processes of law. Nobody had forgotten Eighteen B and nobody was happy. The legislation had been introduced after the final and perhaps most sensational of security scandals, and Members had been conscious that their constituents were in no mood for another. So the Bill had crept into birth as an Act, but only just. It had never been invoked, and Sir Jeremy hoped, and devoutly, that it never would be. The hope sprang from a great deal more than an academic respect for the traditional liberties of the subject. Sir Jeremy was a very senior civil servant and a very experienced one. He did not wish to recommend to a Minister, a Minister lacking a steamroller majority, a course which the Minister would necessarily find unpopular. He knew precisely what would happen.

He decided to temporize. ‘That would be for the Minister,’ he said.

‘Of course. But in the Minister’s absence perhaps it wouldn’t be premature to consider a recommendation to him.’

‘It would be entirely premature.’ It was Professor Wasserman speaking. He struck the table with a hairy hand. The gesture had an opulence which the others would not have permitted themselves. They looked at him with tolerance. He wasn’t entirely English, they were thinking privately—a Jew in fact; an exuberant creature but immensely able. Indispensable—indispensable to Amalgamated Steel. ‘It would be a deplorable precedent.’ He struck the table again. Even the palm of his hand, Sir Jeremy noticed was a little hairy. He looked away quickly, but not in disgust, for he had seen something which he had not expected to see. Wasserman’s lips were parted over his formidable teeth. He had given Sir Jeremy an enormous wink. ‘It would be a precedent and a dangerous one,’ he repeated.

The Commission considered this. They were eminent men, careful men, officials reared in a tradition of caution. They were thinking that the special powers had never been used, and that a precedent wasn’t something to be lightly embarked upon. A precedent, a new departure, something unknown . . .

It was evident that Holsteiner was speaking for the sense of the meeting. ‘That is certainly for the Minister,’ he said. ‘And for Bates to decide upon his recommendation or otherwise.’

‘Precisely,’ Wasserman said firmly. Sir Jeremy looked at him again. Wasserman had begun to sweat a little. He was wiping his hands on a very expensive handkerchief. But he was evidently an ally. ‘We must allow the situation to ripen.’

There was a general relaxation around the table. The situation must be allowed to ripen—ah, there was something upon which experience and a ripe judgement could fasten, something familiar. There were plenty of precedents for allowing the situation to ripen.

‘But surely . . .’ Elton insisted.

Holsteiner interrupted him. ‘I think we must await events for a little,’ he said. ‘This is hardly a decision to take ex hypothesi.’

‘Quite,’ somebody said.

‘Precisely,’ Wasserman said again. His tone was solemn, but he exposed to Sir Jeremy the ghost of that first tremendous wink.

Charles Russell was walking with Nichol from the Commission’s meeting. He was grinning. ‘Thank you, William,’ he was saying, ‘thank you for getting me away like that. It was really very neat.’

‘Not at all. Do you ever read the Agenda, by the way?’

‘Not if I can help it.’

‘Then it will have escaped you that the next item was financial. The estimates, in fact.’

‘Then thank you doubly.’

‘And doubly not at all. I was in no mood myself to discuss money. To begin with there isn’t any. They’ve got their Slow Burner, and the tap is off. There isn’t a penny for anything I’m interested in. I’ve become a production manager, not a scientist. It’s one of the things I particularly resent. I’m bored with it.’

‘I must say you don’t look in a very good temper. Charles Russell hesitated. ‘Money or the lack of it was one thing . . he reminded. . .

‘And this damnable suspicion is the other. Suspicion, Charles—it isn’t an atmosphere I care to live in.’

‘I thought you handled that extraordinarily well. You headed them off beautifully.’

‘By saying that I could have simulated epsilon myself? But it’s true you know. I dare say I could if the idea had occurred to me.’

‘Exactly. But it didn’t.’

‘And how do you know? I’m just as suspect as anybody. In principle, that is.’

‘But we’re not working on principle. At least, I’m not.’

Then what are you working on?’

Charles Russell hesitated again. ‘Suspicion,’ he said finally, reluctantly. William Nichol replied with an expletive. It sounded remarkably like ‘Bah.’

They came to Russell’s office. ‘You can’t have lunch with me, I imagine?’ he proposed.

‘I should have been delighted. But I cannot.’ Nichol smiled, his good humour returning. ‘I have an engagement,’ he explained. ‘A very pleasant one.’

‘A glass of sherry, then?’

Nichol looked at his watch. ‘With pleasure,’ he said. ‘My engagement was genuine—I should have left them in any case. The estimates made it a little earlier, that is all. But we still have time for a drink.’

In Russell’s untidy office there was an excellent sherry. Nichol drank it with a proper respect, but he looked from time to time at the clock. Russell caught his final glance. ‘A lady, I gather,’ he said smiling.

‘But naturally. Didn’t I decline your own invitation?’ Russell bowed. ‘I thank you,’ he said.

‘And a very charming one. You know her, by the way.’

‘Indeed?’

‘Indeed. She’s Bates’ driver.’

‘Good God.’

‘What do you mean, good God?’

‘Bates’ driver is also Parton’s wife.’

‘So I have discovered.’

Charles finished his sherry at a gulp.

‘That is no way to treat a decent wine,’ Nichol protested.

‘I know it. But my dear William . . . Mrs Parton . .’

‘What of it? She’s a lady, Charles, if you will forgive the word. I like her. I’ve seen a certain amount of her and I intend to see a great deal more. If she will let me, that is.’

‘But Parton is . . . is suspect. You said so.’

‘I did. You more or less made me. Are you telling me his wife is the same?’

‘By no means.’ Charles Russell refilled the glasses. ‘By no means,’ he repeated. ‘We know a little about Mary Parton, of course; we are obliged to. We should have to know something of your own wife, William, if you still had one. I know it was six years ago, so I can speak of that. But William . . .?’

Nichol interrupted. ‘You had better tell me,’ he said. He looked again at the clock. ‘And if you could condense a little,’ he added, ‘I should be grateful.’

Russell obliged. ‘War-time marriage,’ he said telegraphically. ‘Opposites. Disastrous. Parton you know about—clever as a monkey, ambitious, Red Brick. Far, far to the Left. And his wife was the opposite of all that. Anglo-Irish. Broken-down Anglo-Irish. Dublin glass—Dublin you will observe, not Waterford—and grocers’ sherry at best. Afternoon tea on magnificent silver and not enough to eat. Bits of beautiful furniture sold surreptitiously. An elegant, a rather futile decay. I suppose Ellis Parton seemed better than that. It was a bargain, I imagine.’ Charles Russell appeared to hesitate. ‘It was a bargain,’ he repeated, ‘and then . . . then it wasn’t any longer. My guess is that she found she couldn’t keep it. Parton would resent that—Parton especially. He isn’t a gracious man—not a man to forgive an injury. I hear there’s been trouble about a divorce. Parton isn’t—he isn’t exactly a gallant.’

William Nichol rose. ‘Thank you,’ he said. ‘But it makes no difference.’

‘Then I wish you a pleasant luncheon.9

‘And I wish you good hunting at Dipley.9

Russell went with Nichol to the door. ‘Where are you going to eat?’ he asked idly.

Nichol smiled impishly. ‘At Bernardo

’s,’ he said. ‘At Bernardo’s, since Mortimer was good enough to recommend it.’

The restaurant to which William took Mary Parton was something short of fashionable. He had chosen it because the food was excellent and ample, and it was his intention to provide an excellent and an ample meal. Women living alone, he knew, seldom took the trouble to cook properly, and accordingly it was their menfolk’s busines to see that they ate rather more than adequately when the opportunity occurred. Nevertheless it was necessary to be careful. Take a woman to a chop house, Nichol reflected, and, however hungry, she was likely to be put off. Or confront her with cooking too elegant, and she was apt to choose snails and a meringue with an ice in it, which left her with little advantage over the boiled egg which she would probably have achieved for herself Nichol had a poor opinion of women as judges of food, and he had taken some trouble in choosing Bernardo’s. He knew there were strawberries, deep frozen; but they had to be thawed very slowly . . .

He had telephoned the day before.

Now he was telling himself that he hadn’t wasted his time. He had persuaded Mary Parton that hors d’oeuvre did nothing but blunt the appetite and had diverted her to a generous helping of smoked salmon. A quick exchange with the waiter in his own language had limited the bread and butter which went with it to two tiny slices and had arranged that the grill, when they visited it, shouldn’t be too grossly stocked. Mary had chosen a very creditable steak. ‘No potatoes,’ Nichol said firmly. ‘Watercress, of course, and French mustard. And a salad separately.’ The grill chef bowed and they returned to their table. The steak arrived and a sole for Nichol. He dealt with it quickly and with astonishing neatness. Mary ate her steak. ‘Cheese?’ William suggested when she had finished. He was in no way hopeful that Mary Parton would agree to cheese, but he was exercising a simple cunning. Strawberries and cream were what he had arranged, but offer them directly and they might be refused. Whereas if something else had been declined . . . ‘Cheese?’ he suggested again. Mary shook her head. ‘Then strawberries,’ Nichol said, ‘and cream.’ He intended the impression that the idea had come to him suddenly. But his voice was eager. ‘Thank you,’ Mary said quickly, ‘I should love some.’ Nichol made a signal to the waiter. The waiter smiled and brought them strawberries and cream.

Slow Burner

Slow Burner