- Home

- William Haggard

Venetian Blind Page 2

Venetian Blind Read online

Page 2

Wakeley murmured something vague, something professional. He replaced the receiver. He didn’t believe it.

Nevertheless on Thursday Palliser’s manner surprised him. He’s a very good actor, he thought – an excellent Minister and perhaps a brave man. Well, we shall see.

He looked about him at the Minister’s room, for it wasn’t what he had imagined it. It was evident that the furniture wasn’t public property, and Palliser’s private taste had moved some distance from Midlothian. It was very good indeed.

Palliser met Wakeley standing. In the Minister’s room, on his own ground, he was decidely impressive. He wasn’t a big man, but his clothes, as he stood in them, were worth a hundred pounds. But, though he was pleased to be a Minister, he wasn’t offensively pleased with Gabriel Palliser. His face, a little sardonic, creased into a smile. ‘Sit down,’ he said; he passed a cigarette box. ‘Sit down and listen.’

‘At your service.’

Palliser lit the cigarettes. ‘I doubt if you believed me the other day.’

A partner in Travers and Bliss didn’t need to spar. ‘It doesn’t matter what I believed.’

‘It was true, though. I’m not in any trouble — not privately, that is. And I have a lawyer of my own.’

‘Then I don’t think I should wish . . .’

Palliser chuckled. ‘You misunderstand me. I didn’t in fact ask you to call as a lawyer. If you feel I have taken an advantage, I apologize.’

Richard Wakeley was silent.

‘I asked you to call as a man. There you could help me.’

‘ I’m not a politician, you know.’

‘You are not. You couldn’t help me if you were.’

Wakeley sighed. ‘You’re being very mysterious,’ he said.

‘I’m afraid I am. And shortly you may think me more so. . . Have you heard of the Security Executive?’

‘Naturally.’

‘A man called Colonel Russell is the head of it. He retires in six months.’

‘Yes?’

‘I want you to take his job.’

Richard Wakeley stared at the window, his lean face impassive. ‘With respect,’ he said finally, ‘you must be crazy.’

‘Perhaps. . . You wouldn’t care to hear how I got that way?’

‘It would certainly be interesting.’

Gabriel Palliser turned his chair from the desk. ‘Security,’ he said, ‘is hell. Counter-espionage has a formidable mystique, but it’s guesswork really, at any rate at the higher levels. And nowadays you have to guess right. The penalties are appalling.’

‘I can see that.’

‘You have to guess right. Which means the right man doing the guessing.’

‘Who couldn’t conceivably be me,’ Wakeley said promptly.

‘I think it might.’

Richard Wakeley was silent again and Palliser went on. ‘Charles Russell,’ he said, ‘was something special. He had it both ways: he ran the machine and ran it beautifully – the files, the dossiers, the interminable cross-checking. All that is essential; it’s nine-tenths of the job, and it wouldn’t be difficult to find a man to carry it. But it’s the other tenth, nowadays, that counts in the pinches, and for that Russell had a flair. A nose. He smelt things.’

‘I’m beginning to smell things too. I can’t say I like them.’

‘That’s largely your virtue.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t follow.’

‘Has it occurred to you that a great many people like bad smells? Like suspicion?’

‘I must believe it.’

Took across the ocean.’

‘I did.’

‘And what you saw shocked you?’

Richard Wakeley nodded and the Minister rose; he began to pace the room. ‘You begin to understand?’ he asked.

‘I can understand that you don’t want to put the wrong sort of man in the Security Executive.’

‘Precisely. The trouble is to find the right one. Charles Russell, as I say, is something exceptional. He has a nose for the suspect but he detests suspicion; he’s a humanist, a liberal in the oldest, the best sense. I can trust him. You can’t trust many, you know, when it comes to that sort of power. I’m afraid Lord Acton was wrong; it isn’t absolute power which corrupts absolutely; it’s power undefined – power to act on suspicion. There was a man in here a year or two ago, somebody from the Indian Police. He was after a job in the Executive, quite an important one: not just a job on the papers – collecting information, assessing it, cross-referencing. He could have done that, I expect – dozens can. No, he wanted the sort of job where he would have had to guess. And I didn’t think him fit for it. He was experienced enough; quite distinguished, I imagine, in his squalid way. But he didn’t convince me – as a man, I mean. As a human being. I didn’t trust him. He got another job, though. In South America.’

‘What happened?’

‘Somebody slipped a knife in him.’

Richard Wakeley laughed. ‘As a salesman,’ he said dryly, ‘you have something to learn.’

‘Our Indian Policeman is irrelevant. I mention him only as an example of the difficulties. I want a man who will act on suspicion – often, nowadays, it’s imperative. But when he does I want to feel that he is acting with – with reluctance. Not relishing the stink of it, but holding his nose.’

‘I should do that all right. I’m a lawyer.’

‘But rather a special sort of lawyer.’

‘Yes . . .? In what way?’

‘You’re Travers and Bliss, aren’t you?’

‘I can’t think you mean to be rude.’

The Minister returned to his chair. ‘I do not,’ he said. ‘I . . . This is extraordinarily difficult. It’s important though, or I wouldn’t be floundering in it. May I ask you a question?’

‘I may not answer.’

Gabriel Palliser lit another cigarette; after a while he said deliberately: ‘You’re an Officer of the Court.’

‘I am.’

The Minister leant forward. The gesture was unrehearsed, unstudied, and by that the more effective. ‘When did you last think of it?’ he asked.

Richard Wakeley was astonished; he thought the question more than a little unfair. Finally he said slowly: ‘I don’t have to remind myself of my formal position to do my daily job.’ He was conscious that it sounded rather pompous.

But Palliser did not press the point. ‘You’ve answered my question,’ he said. ‘You’re a lawyer — a shrewd one, if I may say so, or you wouldn’t be where you are. Also you’re a civilized man. That gives me one half of what I need and find so hard to discover again; that gives me safety – the assurance that the sort of power I’m offering won’t corrupt. It won’t corrupt because your training, your background immunizes you. But I need more than that; I need, when it is necessary, action. Immediate, detestable action. So you see I am between two stools. I don’t want an Indian Policeman and I don’t want the Vinerian Professor or a High Court Judge.’ The Minister, for a moment, was very serious. ‘A partner in Travers and Bliss would suit us very well.’

‘I should be flattered, I suppose, but I’m afraid it won’t be myself. Anyway, you know nothing about me.’

Gabriel Palliser dropped his eyes. ‘You do us an injustice,’ he said.

‘You mean you’ve been poking about, prying into my . . .’

The Minister smiled his most deprecatory smile. Damn him, Wakeley thought. But he found that he was smiling too. Damn him, it wasn’t surprising that he was a Minister. One must allow him charm. Even as a boy . . .

‘This is a serious matter,’ Palliser said, ‘and a serious offer.’

‘Then I’m sorry I must disappoint you.’

‘You wouldn’t even try it? For six months or so? Naturally there would have to be a period for the takeover.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘You’ll realize that we’re up against it. If Russell had had any possible successor in his own organization . . .’

Richard Wakeley shook his head.

‘I don’t want to sound like a blackmailer, but it wouldn’t make any difference if I told you that we’re in serious trouble? I mean the Executive is. Something is leaking, something of enormous importance. And we can’t spot the leak.’

‘It would alarm me, of course. I read the newspapers.’ Richard Wakeley smiled again. ‘And,’ he added, ‘I can guess. That was your own suggestion, you’ll remember.

It would alarm me, but it wouldn’t make me think I was your man.’

I can’t persuade you?’

‘I’m honestly afraid not.’

‘If it’s the firm that worries you ...’

‘It isn’t.’

‘Then if I may ask . . .?’

Richard Wakeley considered; he was perfectly certain, but he didn’t want to sound pompous again. At last he said lightly: ‘In one of those Oriental empires there was supposed to be an official called the Director of Dangerous Thinking. The “Director” amuses me but the job wouldn’t.’

The Minister rose again; he was evidently disappointed. ‘We must have luncheon sometime,’ he said.

‘Of course. Whenever you like.’

Gabriel Palliser held out his hand. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said.

‘I’m sorry too. But thank you for the compliment. Richard Wakeley was looking doubtful. ‘I suppose it was one.’

He took a taxi back to his office, arriving at five minutes to noon. He washed his hands, his mind a careful blank. It was a professional trick, but he attached importance to it. It wasn’t that he was uninterested in his conversation with Palliser: on the contrary it had intrigued him, making him more curious than he could remember. Later he would consider it, rolling it around in his mind. But not now. Now, in five minutes, Gervas Le

at was coming to see him, and Gervas Leat was an Important Client in capitals as large as private fancy suggested. Originally he had gone to old Sir Maurice but, a year or two ago – Richard Wakeley had never been told the details – he had somehow become his own. And that he was coming was another reason for the blank, the wholly receptive mind. He hadn’t announced his business, and Gervas Leat had fingers in too many pies to make it useful to speculate. You received Gervas Leat; you listened very carefully; and, if it were at all possible, you did as he suggested.

Wakeley sat down at his desk, and punctually, at twelve exactly, Gervas Leat was announced. He came in easily, smiling a smile which was something more than social. He was pleased to be calling on Richard Wakeley, and he knew no reason to hide it. He was dressed a little casually – less formally, for London, than the eight thirty-sevens would have ventured – but his careless clothes pointed a distinction which he had certainly never studied. He had blue eyes, grey hair, and a figure which it was evident he had never had to worry about. He must, Wakeley thought, be just about fifty. His hair apart he didn’t look it.

He took out a silver cigarette case, perfectly plain. Richard Wakeley declined. ‘What can we do for you?’ he inquired.

‘You can listen patiently, my friend.’

‘Don’t we always?’

‘You do indeed. I suppose a solicitor’s office is the protestant’s confessional.’

‘We charge a great deal more, though.’

‘I pay it gladly.’

Richard Wakeley laughed. ‘Seriously,’ he suggested. Gervas Leat lit his cigarette. ‘Two things,’ he said. ‘The first is business – strictly business. The second you will probably think mad.’

‘Let’s take the first then.’

‘I want to give Margaret a present.’

‘Good heavens,’ Wakeley said. ‘Another one?’ He hadn’t meant to sound surprised.

Gervas Leat didn’t seem to notice. ‘You’re thinking about that Trust,’ he said. ‘Forty thousand, wasn’t it? You and my accountant are Trustees. . . Discretion to appoint to Margaret and to two others you were kind enough to suggest, but who aren’t in fact intended to benefit.’ Gervas Leat chuckled. ‘So we all had a little chat and you appointed to Margaret.’

‘We did.’ Wakeley was thinking that forty thousand wasn’t chicken-feed even to Gervas Leat. He was wealthy no doubt, but hardly as indecently as people seemed to think. Money he had made, but only to spend.

‘I’m grateful. It cost me very little, you know. What did that accountant say? Two thousand, more or less, in Margaret’s hands and a few hundreds, after tax, in mine?’

‘That was about it.’

‘It was a bargain.’

Yes, Wakeley reflected, it had been a bargain. Travers and Bliss did a good deal of that sort of thing; they were very expert at it. Tax avoidance and tax evasion – they were perfectly distinguishable: a Judge had said so. Not everybody seemed to feel that way, though, That extraordinary fellow they had had – what the devil had been his name? He had had a job in Cape Town and had chucked it for some reason he was reticent about; he owned a degree in law and now he had wanted to serve his articles. He was much too old really, but Travers and Bliss had accepted him. He had been pretty good too – competent and hard-working and conscientious. How he had been conscientious! Also he had been impractical and disapproving. These admirable arrangements – perfectly legal and proper Wakeley reminded himself – these ingenious arrangements at the Revenue’s expense; he had looked askance at them, he had started to give little lectures about them. They weren’t, he had admitted, illegal; he wished to make it quite clear that he realized that; but. . . Poor chap. He had been so certain that, when he had passed his examinations, Travers and Bliss would have something for him. Wakeley remembered his face when they told him that they hadn’t. Poor fellow. Poor earnest little man.

Richard Wakeley smiled a little wryly, for he was remembering what, an hour ago, Gabriel Palliser had been implying about Travers and Bliss. He would have been offended if he had been a man to take offence. Instead he was smiling, thinking that the Minister was nobody’s fool. Not like. . . what on earth had been the fellow’s name. . .?

Anderson – that was it: Lionel Lowe-Anderson. Wakeley had heard that Gervas Leat had found him a job. Naturally it wouldn’t be a good one.

‘It was a bargain,’ Leat was repeating.

‘And a handsome one, if I may say so. Two thousand a year – that’s pretty generous for a stepdaughter. I know she took your name . . .’

‘I don’t,’ Gervas Leat said slowly, ‘I can’t think of Margaret as a stepdaughter.’

Richard Wakeley was conscious of an emotion which he resented. He wasn’t prepared to examine it but its existence was disturbing. People gossiped abominably: one tried not to listen but it was impossible not to hear. And it was nothing to do with him – nothing in the world, he insisted. But. . . but. . . ‘I don’t think of Margaret as a stepdaughter.’ Of course that was a perfectly innocent statement. Perfectly innocent, or perfectly damning.

Forty thousand pounds – it was very generous even for a rich man. And now he was talking about more.

Damn it, it was nothing to do with Richard Wakeley.

Nevertheless he was astonished at his tone when he answered. ‘So you want to give her more?’ he was saying. It sounded almost belligerent.

Gervas Leat didn’t seem to notice anything. ‘If you can think of a way.’

‘There are several. There’s a Trust, as you say, but it’s discretionary in theory. The Trustees could go mad and appoint the income to one of the others. Why don’t you give her a lump sum? Outright. It will upset her tax position, naturally. Nevertheless . . .’

‘What would you suggest?’

Richard Wakeley shrugged. It wasn’t one of his normal gestures. ‘Whatever you can afford. That’s primarily for your accountant.’

‘Thank you. It’s worth considering.’

‘Or you could simply give her presents – that would probably be easier. Buy her a car, furs. . .’

Really, this wasn’t the way to talk to a valuable client.

Gervas Leat was laughing. ‘I have,’ he said.

With an effort Richard Wakeley recovered himself; he was more than a little ashamed. ‘Then you will consider,’ he began carefully.

‘I will. I’ll have a talk with Andrews.’ Andrews was the accountant.

‘And let us know what he suggests?’

‘Certainly.’

‘We’ll do whatever is necessary.’

There was a moment of silence whilst Gervas Leat lit another cigarette. Richard Wakeley was unhappy, even a little alarmed. But not that he had behaved rather badly. Margaret Leat, he was thinking . . . To the devil with the Leats! Gervas Leat he admired – yes, admired. He admired him that, respectful of material success, using it, it had never mastered him. Leat was his own idea of what a wealthy man should be, what he himself would wish to be if ever by some accident he became wealthy. Wakeley was pleased to have been asked to Leat’s home, for its casual elegance fascinated him. He had decided that a calculated elegance was merely tiresome.

It had been at Beltons that he had met Margaret.

But Leat was speaking again. ‘That deals with what is strictly business,’ he was saying, ‘It takes us as far as we can go for the moment. But you’ll remember that there was something else.’ He smiled his easy smile. ‘I said you’d probably think it mad.’

‘I shouldn’t admit it.’

‘You can if you like.’ Gervas Leat lit his third cigarette. He smoked a good many in the day, but his hands were unmarked for he took excellent care of them. ‘I’m an engineer,’ he said slowly. ‘It isn’t how I made money, or not what matters, but it’s how I was trained. I was trained as an engineer and it still conditions me. I think as an engineer.’

Richard Wakeley began to listen very carefully: Gervas Leat wasn’t given to talking about himself. This could be interesting, Richard thought, Gervas Leat employed him, five private and satellite senses into a world which he didn’t himself understand. Probably he rather despised it – many men did. So you worked for Gervas Leat, you took your instructions. Also you liked him and he seemed to like you. You admired him and you knew nothing whatever about him. Richard Wakeley liked to label his clients. It was a convenience.

He had just realized that far from tying a label to Leat he was entirely ignorant of him.

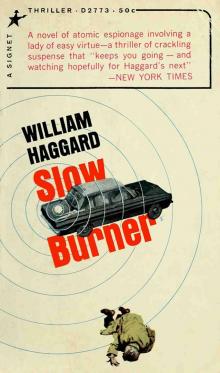

Slow Burner

Slow Burner