- Home

- William Haggard

Slow Burner Page 11

Slow Burner Read online

Page 11

Later Sir Jeremy could remember that he had put the note back again into his pocket; he could remember an emotion which had appalled him; that with an enormous effort he had restrained a vomit; but of conscious thought he remembered nothing until he was aware that the taxi had stopped outside his flat. The driver opened the door, and his expression changed. ‘Are you all right, sir?’ he asked. His voice was concerned. There was a looking-glass in the taxi-cab screwed below a vase of paper flowers, and Sir Jeremy looked into it. His face, he saw, was grey; his hands twitched in spasms which disgusted him; he was conscious that his underlinen was soaking. He forced himself to speak. ‘I have changed my mind,’ he said. ‘Drive me to the Ministry of Development.’

The driver looked doubtful. ‘Is this where you live, sir?’ he asked. ‘I would turn in if I was you.’

‘Do as I say,’ Sir Jeremy rasped. The driver shrugged and climbed back into his seat.

To the Ministry, thought Sir Jeremy. To the Ministry. To his office, to his room. It was there, in the room, for he dare not keep it at home. In his room, in the cabinet in the comer. In the cabinet. Escape. Oblivion.

An astonished night porter admitted him. The lifts, he found, were not working, and shakily, with an effort which drained his being, he climbed to his office. He fumbled with his keys, cursing his trembling hands with words which would have amazed him if he had heard them. Finally his keys came free. He opened the cabinet and took from it his bottle and a tumbler. He drank—greedily at first, then with more deliberation; and then again. He forced himself to look at his diary; nothing tomorrow before ten o’clock. His hand went out again towards the bottle, but he checked it . . . Thirty years—thirty years he had fought for his life. His father and his father’s father before him. Sir Jeremy shuddered. But he had beaten it; he was master, he told himself, alcohol the undisputed servant of the exceptional occasion. Well, this was an exceptional occasion and it had served him; he could feel it still serving him. Disgusting, then, to blind into unconsciousness like a common addict . . . an addict. Sir Jeremy shivered. Nevertheless his hand crept out towards the bottle. He poured himself a careful finger of whisky; then, with something which was half a groan and half a sigh, three more. He drank with relish. In a matter of moments, he realized, he would be insensible. He went into the outer office and found an overcoat; he stretched himself upon the sofa, pulling the overcoat about him. But he discovered that the sofa was unbearable. Deliberately Sir Jeremy moved to the floor. He took a leather cushion from one of his chairs and put it beneath his head. The overcoat he pulled again about him.

In the morning, it occurred to him, in the morning a charwoman would find Sir Jeremy Bates dead drunk upon the floor.

He did not care a damn.

Chapter 6

The cardboard notice on Russell’s door next morning was in large black type. It read: IN CONFERENCE, but the formidable cliche concealed a scene entirely domestic. Russell had his feet on the desk, and Mortimer, who put his feet up in his own room but not in a superior’s, was into his third cup of tea. ‘We haven’t got very far,’ he was saying.

‘We haven’t,’ Russell agreed. ‘All that I feel reasonably certain about is that this apparatus at Dipley is a blind. Of course from our side of the fence it looks a little amateurish: but if somebody wanted to distract us, to distract our attention and our people’s from the dull routine of security to the excitement of pursuit, then perhaps the idea might have its attractions as a red herring—to an amateur, that is: but our resources aren’t so limited that we cannot both continue to watch a suspect and investigate a curiosity at the same time, and I flatter myself that we aren’t so ingenuous as to fall for the simpler varieties of red herring. But I’m not in the least surprised. I know—you know—that over-elaboration, a tendency in the amateur to be too clever, are mostly what keep us a jump ahead of the gun. That and better office work. No, it doesn’t surprise me.’

Mortimer nodded. ‘And in fact,’ he said, ‘Parton’s position wouldn’t be as simple as all that if what he’s aiming at is to get himself out of the country. It’s true that if he’s got the contacts his papers suggest he has it isn’t impossible that he could get himself smuggled out; but he couldn’t just buy a ticket and walk into an aircraft. There are about a dozen of these Slow Burner men who know too much—Doctor Nichol, Parton himself, and a few others. They vary the list from time to time, but Nichol and Parton at least have been on it for years. They must know it too, for any man on the list gets warned not to leave the country without permission. Which is in practice impossible to get. Very inconvenient, I should say, but top scientists nowadays . . .’ Mortimer shrugged; he took a pull at his tea. ‘And these scientists aren’t fools,’ he went on. ‘They aren’t likely to suppose that the authorities limit themselves to requests; they must guess that in practice they couldn’t just catch a boat or plane; they must guess that Security is interested in their movements. So I quite agree that to one of them considering a getaway—an amateur in the business, that is—a blind would probably seem a very good idea. It doesn’t to me because I’ve had blinds pulled on me before. But then I happen to be a professional.’

‘We were talking about Parton,’ Russell said smoothly.

‘We were, sir. And I must confess for no very good reason. This drinking business is a dead end. Naturally I’ve had a word with the young man in question. He was perfectly forthcoming; he admitted knowing Parton; he admitted an occasional binge with him. But he totally denied ever introducing him to Mrs Tarbat or even mentioning her existence. I think he’s telling the truth, and if he isn’t it’s going to be damned difficult to disprove it. Why should he mention Mrs Tarbat?’

‘Come to that, why should you—to this young man, I mean?’

‘That was a little tricky, but it was a risk we had to take. But we don’t want the news that we’re interested in Number Twenty-Seven babbled around the City and the West End, so I told young Peel a part of the truth. I admitted where I came from—I had to—and that we had a considerable interest in Dipley. But I hinted, too, that we weren’t particularly concerned with Mrs Tarbat as such—that she was really a side issue. As I’m still inclined to believe she is. I was very official and more than a little pompous. I appealed to his public spirit, and I think I scared him a little. We have a certain reputation, you know.’

Charles Russell smiled. ‘It can be useful,’ he admitted. He considered for some time. ‘You feel Master Peel will get us nowhere?’ he asked finally.

‘Pretty sure.’

‘And if he’s lying we can hardly break him?’

‘Exactly.’

‘Which leaves us . . . where?’

‘It leaves us suspecting Parton on principle—on the papers. But suspecting him without the slightest lead from himself to Number Twenty-Seven.’

Colonel Russell inspected his nails. ‘He could have found the front door key,’ he suggested.

Mortimer shook his head. ‘And how could he know it was Mrs Tarbat’s?’ he inquired. ‘A key in the street or in a cloak room—it’s a very long way from Number Twenty-Seven.’

‘Then he could have stolen her key or had it copied.’

‘Certainly he could—if he had known it was hers. And how did he know that? We are back on the assumption that he knew her.’

Charles Russell smiled again. ‘I can see,’ he said, ‘that you don’t like any of the obvious explanations. To tell you the truth, nor do I. They raise more difficulties than they solve; they assume, as you say, what we are trying to establish, namely that Parton and Mrs Tarbat are acquainted.’ He thought for some time. ‘Moreover,’ he said finally, ‘we need more than a casual connexion. Suppose for a moment that Peel had admitted to introducing Parton to Mrs Tarbat—where would that have taken us? Parton could have gone to Twenty-Seven. Excellent, that, as far as it would have gone. But this apparatus is quite an elaborate affair, to say nothing of the fact that it needs wiring to the light circuit. Perhaps Mrs Tarbat doesn’t

understand the ins and outs of all this—that’s perfectly acceptable—but why did she let him put it there at all?’

‘You have your finger on it,’ Mortimer agreed.

‘I very much fear that I have. And I very much fear that I am now going to clear my thoughts by inflicting them on you.’ Russell lit his pipe and smoked for a while silently. He returned to Mortimer with an apology. ‘I am sorry to sound like a lecturer,’ he said, ‘but ex hypothesi there are only two reasons why Mrs Tarbat should have allowed the apparatus into her attic: either she is in league with Parton, an accomplice, or he has a handle against her and can compel her to assist him.’

‘I don’t like the first.’

‘Nor do I.’ Colonel Russell was looking innocent. ‘Mrs Tarbat sounds delightful,’ he added. ‘You must arrange to introduce us.’

Mortimer let this pass. ‘And the second,’ he suggested, “still depends upon establishing that Parton and Mrs Tarbat have met at all.’

‘Precisely. To that extent we are beating the pistol. Back to the connexion, then.’

‘Which we haven’t established at all.’

‘But must.’

Mortimer suppressed a shrug, but Russell was thinking again. ‘A very long shot is indicated,’ he said slowly.

‘You can see one, sir?’

‘Perhaps . . .’ Charles Russell drew Parton’s dossier towards him; he turned the pages quickly and finally stopped. ‘Parton was in America in forty-eight,’ he said.

‘He was. That was before he got into the V.I.P. class—before they put him on the Security List. He went with some scientific mission or other. As it happens that was when we first took an interest in him, for he said some very silly things in the States and made some even sillier contacts. The Americans reported them back to us.’

‘So I see . . . I suppose Mrs Tarbat has never been to the States?’

‘I shouldn’t think so.’

‘Ask her.’

‘Now?’

Charles Russell nodded. ‘Now,’ he said.

Mortimer picked up the telephone. Russell could hear the number ringing out. It rang for some time before it was answered. Mortimer asked two questions. He put the receiver down again. ‘Mrs Tarbat was in New York in forty-eight,’ he said, ‘and she denies that she met Parton there.’

‘I expected her to,’ Russell said.

‘Well, it was worth trying.’

‘My dear fellow, we haven’t yet tried. Ring New York.’ Major Mortimer only partly concealed his astonishment. ‘But surely,’ he protested, ‘if she had met him there the Americans would have told us.’

‘But why should they? We are thinking ex post facto. That is bad. We are thinking of Parton as a suspect—a suspect whose doubtful contacts were reported back. Now think of Mrs Tarbat. Because if there is one thing we seem to be agreed on it is that Mrs Tarbat isn’t herself particularly doubtful. The Americans weren’t so interested in Parton that they reported his movements round the clock. Perhaps he had a girl in New York—who doesn’t? Perhaps it was Mrs Tarbat. Perhaps . . . perhaps. The range, as you say, is very long indeed. It’s enormous. But telephone to Levison just the same.’ Major Mortimer started to rise, but Russell checked him, smiling. ‘Take it easy,’ he said; he glanced at his watch. ‘Nearly lunch-time here,’ he said, ‘but barely eight o’clock in New York. I can remember when that five hours’ difference played into our hands and I can remember when it was disastrous. Levison gets down to town at about half past nine—half past two on our time. Telephone then. If he isn’t there, telephone his apartment. If he isn’t at home, ring the Harvard Club, and if he isn’t at the Club try the Metropolitan golf courses. But get him if you can. Let us give him an hour to work that filing system of his—say till tea-time. Then come and tell me . . . if there’s anything to tell, that is.’ Charles Russell sighed. ‘I repeat, it’s a very long shot.’

No office cleaner found Sir Jeremy that morning upon his floor, for he woke early. His beautiful clock told him that it was half past five. He pulled himself to his feet, surprised that he was not stiffen But the mirror on the wall was without compassion; it told him that he must get himself home immediately. He locked away the bottle and his glass—it was unpardonable he thought now to have left them out—and restored the cushion and the overcoat to their places. He looked in the glass again; he was drawn and grey and his legs felt as though they had been filleted; but he discovered that his mind was clear. The crisis was past. He was without regrets.

Half past five. The service lift would be working, he reflected, and he weighed the pros and cons of using it. From the stairs he shrank, for he was by no means sure that he could manage them without disaster. But if he used the lift he would almost certainly be seen—Sir Jeremy Bates, grey and unshaven . . . Well, he could have fallen asleep in his chair working late at his papers. He looked for the third time at the mirror. His image returned his inspection with an evident doubt. This, it told him, is not the appearance of a senior official overtaken at his desk by sleep. Sir Jeremy shrugged. He remembered that after all the night porter had seen him coming in, and he decided to chance the lift. In the hall he slipped from it successfully and took a taxi to his flat.

His manservant received him without question or comment, and within Sir Jeremy rose an unreasonable anger. Confound and damn the fellow! His lack of interest was an insult. A gentleman’s gentleman—the convention had survived, the convention of the English manservant, secret, uninquiring, impersonal. Sir Jeremy felt his anger increasing. He looked at his servant with something which was almost belligerence; deliberately he sought and held his eye. ‘Run me a bath please, Wilson,’ he said. ‘And I shall need a pot of black coffee.’ He paused. ‘I have had an indiscreet evening,’ he added. His voice was almost provocative. Wilson replied that he understood. He withdrew, and Sir Jeremy could hear him busy in the bathroom. A fossil, he thought furiously, a jellyfish. He controlled himself with an effort which he realized was altogether too considerable. It was absurd to be angered by a trifle; it was ridiculous to be so easily upset—ridiculous and, he recognized, dangerous. ‘I must watch myself,’ he muttered as he slipped into his bath. The temperature was exactly right. It would be, he thought sourly—Wilson would see to that. ‘Damn Wilson,’ Sir Jeremy said aloud. ‘Damn his eyes.’

He shaved in a mirror which a miniature fan, blowing a jet of warm air, kept free from steam. The gadget was one of his few luxuries. The tiny whine of the fan, the hiss of the air as it left the edges of the looking-glass, soothed him. His body soaked in the heat of the bath and he began to feel better. Nevertheless, he told himself, I will not think just yet. Not yet. And, principally, I will not feel; I will not allow myself emotion. God knows there is thinking to be done, but thinking and feeling did not go together, did not marry, did not live happily, were not fruitful, parted, lived separately, like Jeremy and Barbara Bates . . . Sir Jeremy realized that he was almost asleep. Reluctantly he collected himself. A movement of the leg, a twist of his toe on the tap, and the bath would have been hot again. It would have been pleasant to stew a little longer, luxuriating, feeling his nerves relax. Instead he pulled himself upright and reached for his towel.

His body was still as lean as a wasp’s, his stomach as hard as a boy’s. At school he had been a waterman, and in later life most watermen went to a prodigious fat. It had been lucky, perhaps, that he had not, for of late he had had no time for deliberate exercise. But it was not entirely luck. Sir Jeremy took excellent care of himself; he never guzzled. He had eaten, the night before, the best part of a grouse, and it had been practically an orgy.

He rubbed himself vigorously, thinking that his figure wasn’t at all too bad for a man of his age. He was greying a little, he noticed, about the chest, but it was a good chest, small-nippled, wide, almost Athenian. His shoulders were wiry and his arms still smoothly muscled. There should be women, not Barbara, but women of position, women in their prime, elegant, even ardent women who would not find Sir Jere

my impossible. If William Nichol . . .

This would not do, he told himself. Not at all. He dressed quickly and went into the living-room. His coffee was upon a round table by the fireplace. He saw that Wilson had taken him at his precise word. Wilson was being infuriatingly tactful. There was a single cup, and sugar, and black coffee in a silver pot.

Sir Jeremy drank it gratefully.

He considered that the circumstances justified a taxi to the Ministry and he took one. Marshall, as he expected, had arrived before him and his desk was piled high. He stifled a sigh, forcing himself to concentrate. He knew the penalty of falling behind even for a day.

He worked on grimly till lunch-time, arranging for a tray to be sent in to him. He did not feel like going to the Club—certainly not to the Club. But, lunch over, he allowed himself to think again. He did not wish to; he did not feel sure that he was capable of thought. But he was conscious that he must make a decision and that he must make it quickly.

He drew from his pocket the note which Schmidt had given him; he read it again, and at once, rising from the pit of his belly, he was aware of an increasingly familiar, an increasingly unwelcome emotion. It was an unreasoning fury, an affair of the body, and with his reason he fought it, for he knew that he could not with safety continue these surrenders to his senses. There was thinking to be done, and the pressing necessity for a decision. The expense of spirit necessary to control these rages had begun to alarm him—the effort was becoming intolerable. Nevertheless he made it. For a man already under pressure the overdraft upon his resources was considerable. He knew that anger, the blind physical rage which a chemist could measure by the adrenalin pumping into the system, was no asset but an unrequited liability. And he could not afford unnecessary liabilities. He fought himself grimly.

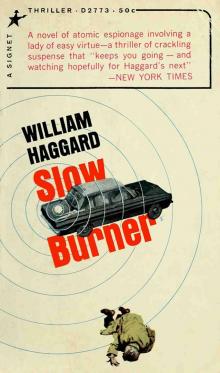

Slow Burner

Slow Burner